On the Human Condition

Text by Andreia Garcia

Part I

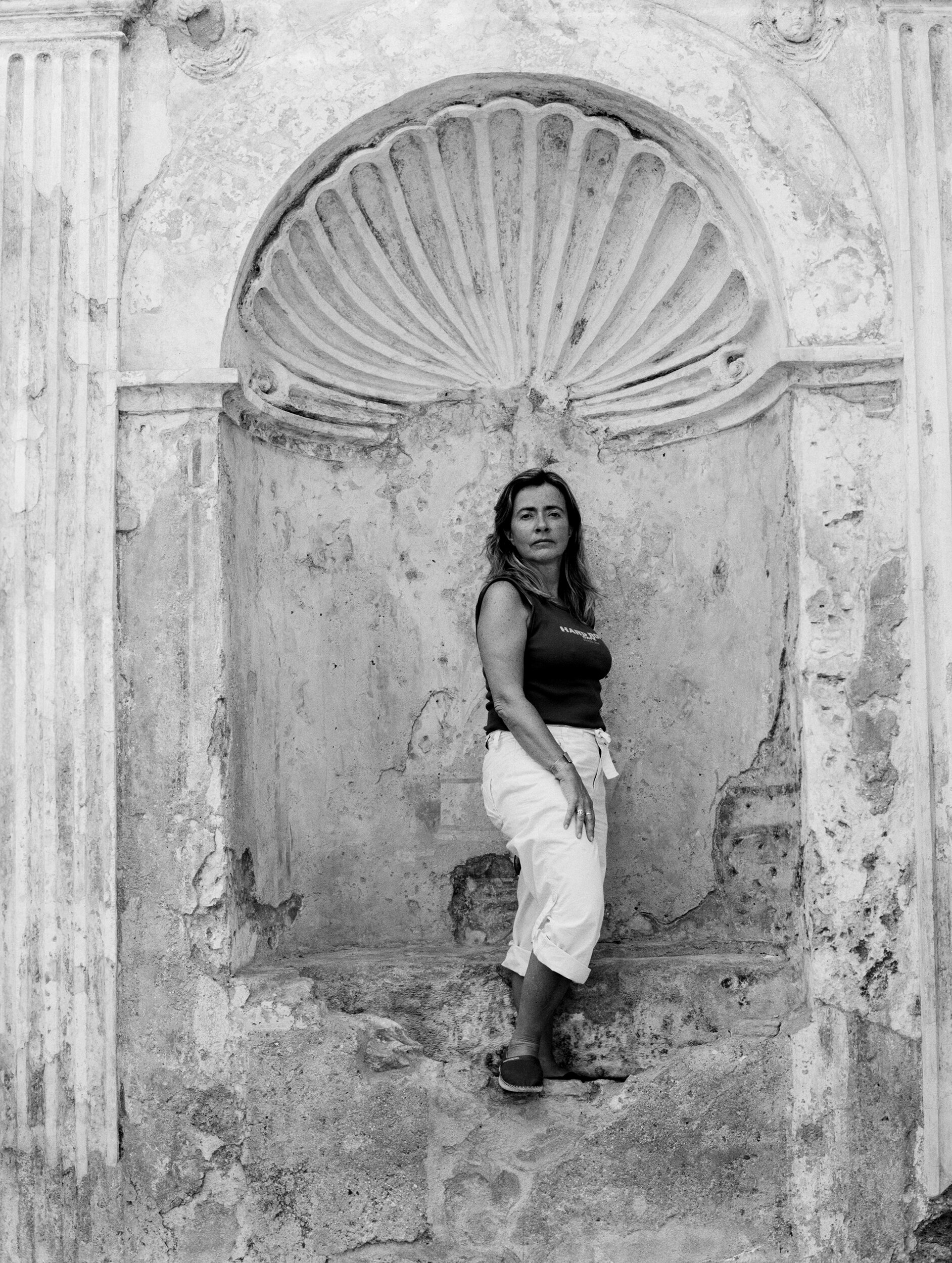

On the human condition. On the remains of a dialogue between the Classical and Contemporary History. Times that sometimes overlap in an assertive dialogue. Constellations of possible gestures on the commonplaces of Humanity. From vice in its most bohemian facets to the silent scream of a sea largely uncaptured. This exhibition issues a firm impression and a wedded gaze, it talks of read allegories and affections whose emotional dimension never wavers in intensity or conforms to the commonplace. Without ever needing to reflect on reality, it outlines the pattern of Tiago Casanova’s language, fiction converted into an experience of truth, of multiple truths, of what remains after truth. We do not know if he drowns the experience of the voyage or if produces a timeless refuge, but there is something imagined in his narrative. Something that is beyond Classical Architecture’s metaphor for a society that still pays homage to the political gods that make us hostages to a new slavery. The marked maintenance of a backbone without vertebrae, of a history somehow akin to kitsch that has been awkwardly implanted in the drama of subjective legends, captured by camera lenses. Columns from a distant time that shatter and carry the fragments of men. These are the heirs of tomorrow’s migrations. The two-tone screams separate the boat’s horn and the gnashing of teeth. We hear the silence of the night. Luxury and barricades expose their safest, but less appealing side. For its part, the hollowness of solitude — on this lost, deep, dark sea — evokes the idyllic impression of an encounter with the most perfect of souls.

Part II

Greece’s philosophical setting has always been conducive to reflection. Once, this was the most favorable context for the emergence of a rational theory for Urbanism. Miletus is one of the most curious examples of a Greek mythological city that refers to conceptual models, presenting an irregular layout at its physical limit. Characterized by the orthogonality of its regular urban blocks, it adapts to the winding contour of the cape upon which the coastal city is implanted. It is precisely here, in the confluence of sea and urban layout — the city’s defining elements — that we can find a parallel between a time that goes well back to 405 BC and Tiago Casanova’s artistic gaze in 2019. In the same Greece, but in different temporal contexts, he highlights the importance of the place of the event. The stage of the social, economic, and political scene can be anywhere, not just at the center of a city. In the case of the locus narrated in the exhibition, as well as in the city here referred to, the sea is a living urban heart, a kind of new Agora. In this sense, between the place of the scene and these two temporal contexts, the place of the theater must be evoked. This text identifies with a theater that looks at dramatic representation as a manifestation innate to the human being that precedes Greek theater.

The place destined for action does not have to exist as a physical structure and can include the natural scenery around it — city, sea, mountains or sky. We can also say that in this show, Which Way the Wind Blows, one can rediscover the meeting place between gods, humans, and nature. However, there are some concerns. Grimal calls our attention to the necessity of looking at the topography of the theatron’s location. One could consider that these places — the place of the exhibition but also the place of the ancient classical city — are both seen as stages, in line with Boyer’s perspective on the places where spectators experience social reality. However, it is important, and informative, to observe the transformation of the landscape over time and to recall from where new drama spews from. The exhibition establishes a parallelism that reminds us of our role and our place in participating, without exclusion, in this new scene that is enhanced by artifice and partially erased from the dramatic confrontation and the intensity of the tragedy and conflict. Like what Molinari said about Greek theater, but evoking the theory to weigh in the materialization of Tiago Casanova’s gaze, it might make sense to alert to the original meaning of the tragic spectacle as a moment of confrontation between the earthly and the divine spheres. That is, the definition of the tragic space, located between the real space and the represented space. We can evoke the commonplace that can be recognized in the place of tragedy, and in the place of worship, and, finally, in the place where we worship tragedy.

Part III

Only common sense believes in time.

[Illation that resulted from a reading of Vladimir Nabokov’s poem Speak Memory. An Autobiography Revisited (1966), New York: Random House, 1989, p. 139.]

A text divided into three parts and three linguistic tones on the exhibition Which Way the Wind Blows by Tiago Casanova for Galeria Carlos Carvalho, in Lisbon. The exhibition was open from November 16, 2019 to January 11, 2020.

Miletus was the work of Hippodamus of Miletus, who is considered the first urban planner with rigorous scientific criteria that the world has known. Note, however, that the orthogonal planes have an earlier origin and can be found in the cities of Pre-classical civilizations, such as Egypt and Babylon.

Garcia, Andreia - Espaço Cénico, Arquitectura e Cidade. Lisboa: Caleidoscópio, 2016, p. 52.

GRIMAL, Pierre - O Teatro Antigo. Lisboa: edições 70, 2002, pp. 14-15. For the reading of this text, one should understand the meaning of the word theatron as “the place to see”

BOYERM M. Christine - The City of Collective Memory, Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 74.

MOLINARI, Cesare - História do Teatro. Lisboa: edições 70, 200, p. 40.

Translated by José Roseira

Which way the wind blows

Exhibition text by Tiago Casanova

The history of the Mediterranean Sea is vitally important for a proper understanding of Western Civilization’s origin and development. Since ancient times, it has been a prime navigation way for trade and cultural exchange between emergent peoples of the region, the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Semitic, Persian, Phoenician, Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, and Turkish. From the invention of the wheel by the Mesopotamians, to the creation of the first alphabet by the Phoenicians, the introduction of philosophy and democracy by the Greeks, or the invention of astronomical instruments by the Arabs. From China to Europe, through traders, the Mediterranean has been a gateway for goods and knowledge, although it was also through this sea that the slave trade gained ground and still has echoes in today’s societies.

The project that I present seeks to address some of the human relations in the Mediterranean Sea of today, seen from a possible distant future. A sea haunted by myths, gods, legends, wars and sunken dreams, selling itself as an idyllic paradise to tourists. A sea divided, between legacy and future, between religions, modern and ancient myths and economical and social status. A sea divided between tourism and drowned migrants and asylum seekers. A sea that is Nostrum and Vostrum, but also the place of a colossal humanitarian crisis.

My approach to this project stems from my interest in subjective and allegorical readings of the photographic image, in-between reality and fiction. In the time of the Fake News and Post-truth politics facts do not seem to matter any more, but only our affections and feelings. We live in a time where everything seems to already have been represented; the photographic image has never been so abundant.

I saw myself in a distant future, imagining our relation to the realities and myths of today in the same way we, in our present, establish a relationship with our past and history: real and traditional stories embody beliefs regarding some facts or phenomena of experience, often personifying the forces of nature and of the soul. What will be the myths of the future in relation to the realities of today? What facts will be doubted, and what myths will be avowed. A visual narrative about the migrant crisis that does not represent the migrant crisis, the work emphasizes a contemporary society that chooses to ignore visual and political evidence, and prefers to believe that gods can turn people into stone.